Peculiar ratio

Today is the 19th anniversary of my mother's death. I was 19 when she died, and so this day for me marks a peculiar ratio: I have lived as long without my mother as I lived with her. Half of my life I've been someone with a mother, and half of my life without.

Of course, it doesn't feel like two even halves: the last nineteen years have gone by much more quickly than my first nineteen years. As much as I feel permanently marked by that loss, it feels recent, too. I mean, it still sucks. I still feel a sharp tug of envy when I see other people, especially other women, with their mothers.

Here's the thing: nobody is like your mother. Nobody replaces her. There is nobody you can cry in front of with the same abandon, nobody you can fight as hard with, nobody who comforts you in the same straightforward and simple way. Nobody who can call you mean things in Chinese with so much love. Nobody who knows exactly the right things to say and do when everyone in seventh grade except for you is invited to that one party. Nobody who gets how much you will treasure that hardbound anthology of Anne of Green Gables and how you are going to need some time curled up alone with it after you've carefully peeled away the wrapping paper.

And here are the things I wish my mother had lived to see: the garden in our backyard, especially our pomegranate tree. The food we eat, dishes so often inspired by her heritage, and the way Adam cooks it, with so much love and commitment that it can't be anything but delicious to the point of magic. The Internet as it stands today, oh my goodness, she would have hated it and then loved it, embraced its infinite possibility. Today's Pope. A woman candidate for president.

Kamal, more than anything. Kamal, who told me once that he had talked to his grandma who died, but that what they discussed was a secret between the two of them. Kamal, who cries out in joy when I wear bright colors, just like she did. Kamal, who gives the songs of birds meanings like she did, whose big eyes I know she would have gladly drowned in. More than anything I wish she could see Kamal. More than anything I wish she could meet him, babysit him, scold me about feeding him cold things for breakfast sometimes, worry with me over his sniffles and bowels and drive me crazy correcting my parenting.

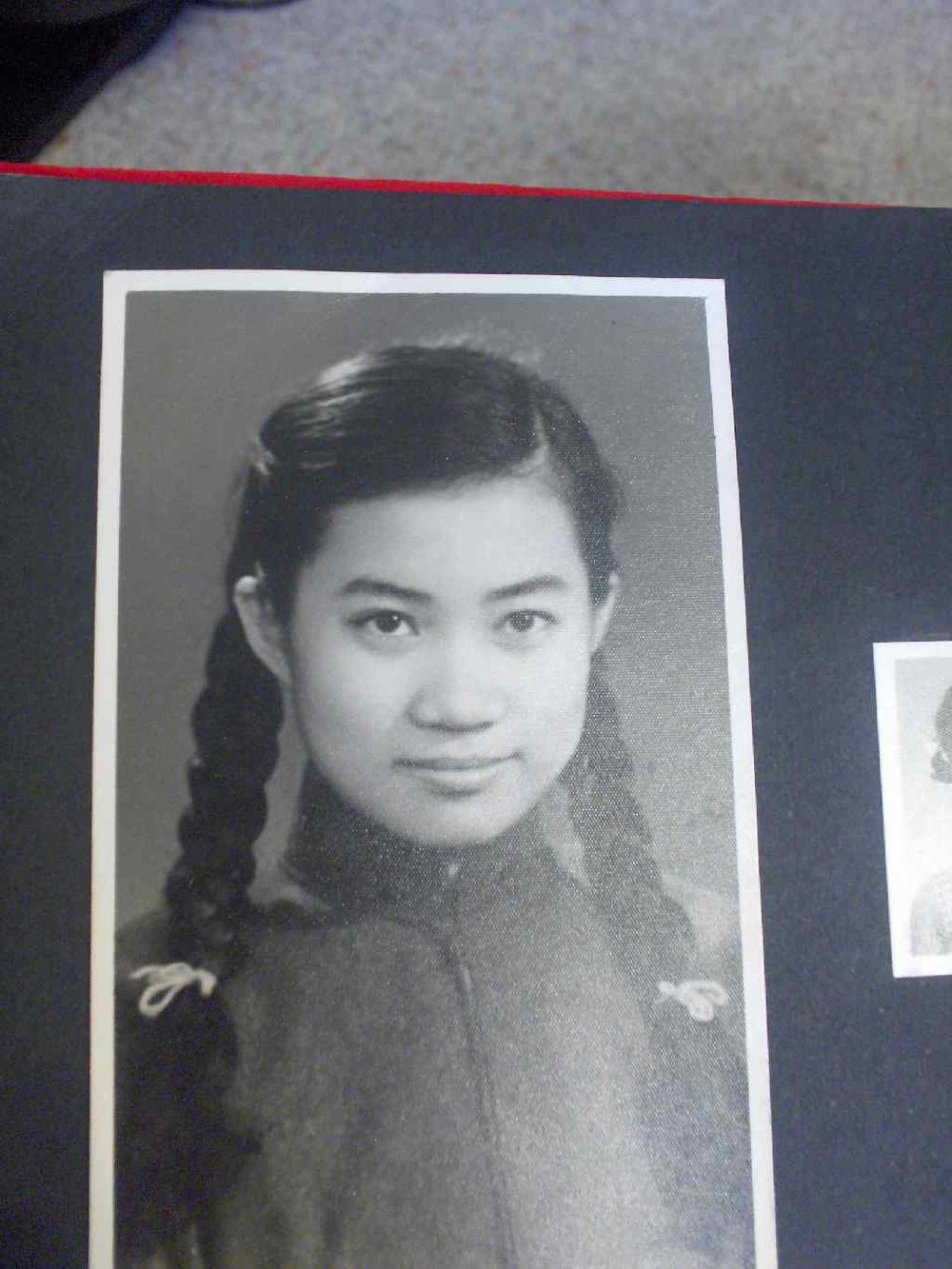

I wish she had taken the RV trip across the country she always talked about. I wish she had traveled across Europe, seen the houses on Cape Cod, tried out yoga. I wish she'd seen how incredibly, improbably, ridiculously beautiful she was, instead of worrying about her weight. I wish she'd been able to hear how many times the word "radiant" was spoken as people remembered her after her death.

She was radiant. Even when she was gaunt and yellow with illness, bent over the kitchen island in pain, she would look up when I walked in and smile at me, full of love, wanting to reassure me. That smile lit everything: our hushed house, the humid valley in which it sat, my path forward after she was gone. That smile! It was like all the light in the world, all the goodness that can exist, was coming through her. Remembering it now--thinking of what it must have taken, to muster that much good in the middle of the agony of failing to resign herself to the end of her life--I don't believe it will ever stop aching, right in the middle of my chest. I don't believe it should.

Because what she did for me, my mother, by dying when I was nineteen years old, was show me how I should live the rest of my life. I was an asshole, like every nineteen-year-old. I was self-absorbed, obsessed with my stupid boyfriend, taking everything for granted. In the midst of watching my mother say a grindingly reluctant good-bye to her life, I drove way too fast all the time, like life wasn't a crazy precious beautiful gift that no one should squander. I argued with her, passionately, about everything, like we were just any teenage girl and her mother and not also a primary caregiver and a dying woman who weighed maybe eighty pounds.

But also, I loved her. After a lifetime of dieting together, I learned to cook things rich with cream and butter and eggs, anything that might tempt her appetite and help her to gain a little weight. I stroked her hair when she threw up, woke up at night to walk her to the bathroom, sat in the doctor's offices with her and got angry on her behalf when she needed me to. I stayed calm for her until I thought I couldn't, and then I found even more calm somewhere, and more and more as the weeks wore on, drawing from a well far deeper than I'd realized existed. I learned what I was capable of, and what I could grow into, if I let myself, if I could work continuously to be honest with myself about my own ego and my own failings.

She asked me--she made me promise--to remember her before her illness, not during it. She said her own mother had asked for the same promise. And I promised. And I think I'm keeping the promise, because I remember, with love and laughter, more about her before her illness than during it.

I remember her following homeless people in order to give them food. I remember her telling me she'd seen a mother cat and kittens in the parking lot down the street, and taking me with her to leave an odorous mixture of milk and tuna fish under the hedges there. I remember how hard she laughed with her sisters, how much she loved Oprah, how she never ever went anywhere without lipstick on. I remember shopping with her--to this day, I've never had more fun shopping with anyone. She and I could spend ten hours in a row at a mall, stopping for lunch, then for coffee and pastries, before heading home with our purchases and throwing a "fashion show" for my bemused dad. (Honestly, if my mother were still alive, I'm not sure I would have become the champion of ethical fashion that I try to be--because it was just too much fun, buying off-the-rack stuff with her.) I remember having my heart broken by mean girls at school and thinking--if I can just wait to cry until I get home to Mom, it will be okay. It will be okay once I'm crying with Mom.

I have other people I cry with now. I am lucky in love, in every avenue of my life--my partner, my sister, my friends, my parents-in-law, my precious and spectacular son. I love them and they love me, and I am grateful for all the tears of mine they've absorbed. I don't mean to diminish that gratitude at all by saying this: it's not the same. I miss my mother. I miss her every day. I want her back. I want to be two grown-up women together, reminiscing, laughing. I want to have learned to fight with her in a smart and productive way, or at least to fight and then make up over coffee and pastries. I want to call her the next time I'm sad and have her help me feel better. I want her to come visit me, to celebrate with me the beautiful life I've landed in, and I want to take her shopping.

If the beliefs my mother held sacred are true, then I will see her again one day. If they are not true, then there is this: I was the daughter of a woman who loved me. I was a daughter who loved my mother, who was gifted the ultimate opportunity to show her that love: to care for her in her last days. There is the love we had for each other, which, no matter how fiercely we could disagree, endures still. There is my sunshine of a child, whose smile is the first I've seen as bright as hers. There is my absolute commitment to living as fully as possible, to tasting every sweetness and exclaiming over every beauty, to taking the roadtrips and singing along to the radio, to dancing in the kitchen and wearing the pretty dresses, because it's the best possible way I can think to celebrate her memory.